These days, city streets are jammed with delivery vans. As e-commerce has surged, so has the number of trucks inching through neighbourhoods, circling for space, and racking up wasted time. For a courier company, each ticket, traffic delay, and failed delivery chips away at profitability. This, as we shall see, is a problem called “the last mile.” And if so-called “last-mile” deliveries are inefficient, they also pollute. Freight already represents nearly a third of Ontario’s greenhouse gas emissions, and by 2030 it’s expected to surpass passenger cars. A solution was needed—and we helped deliver it by cargo bike!

Rethinking the Last Mile: Why Vans Fail Where Cargo Bikes Thrive

The Pembina Institute’s Delivering Last-Mile Solutions study makes a strong case for such a shift. The study concludes that vans are poorly suited to the “last mile.” In logistics, the last mile is the final leg of delivery from a local depot to the customer, where bulk shipments are broken down into individual parcels. This deconsolidation already makes each trip less efficient, since a vehicle is running with light loads and making dozens of short stops. But once you add urban gridlock into the mix, these inefficiencies multiply. In other words, the strange problem with the last mile is that the shortest distance in the supply chain is also the costliest.

The answer, Pembina argued, is to rethink the system itself. Trucks could still carry bulk loads into the city, but instead of pushing them further into congested neighbourhoods, they would stop at micro-hubs. Micro-hubs are small depots set up within a 5–10 km range of the target customers. From there, cargo bikes would take over. Freed from congestion, able to park directly at the door, and supported by short, frequent resupply trips, cargo bikes deliver more packages in less time while also cutting emissions and costs.

Europe’s Proof of Concept: How Bullitts Beat the Van

Not surprisingly, this proof of concept already existed in Europe. In Brussels, the cooperative courier Urbike built its fleet around Bullitt cargo bikes and became the subject of a rigorous study tracking more than 7,000 real-world deliveries. The results of this study are impressive, to say the least. Because a cargo bike can take shortcuts that a van cannot, cargo bikes could run routes that were 30% shorter than vans. Likewise, cargo bikes were also faster, travelling at a consistent 16 km/h, while vans inched at 11 km/h. Finally, cargo bikes solved the problem of the “last steps.” Unlike a van, the study showed that cargo bikes can park within 3 metres of the door on average. The long walk between van and door is simply cut out.

In sum, Bullitts delivered in half the time of vans (48 minutes vs. 99 minutes), at one-fifth the cost per parcel, while slashing lifecycle emissions by 96–98% compared to both diesel and electric vans. Brussels confirmed what Pembina’s modelling predicted for Canada: smaller, faster two-wheelers like the Bullitt are cleaner, more efficient, more profitable, and better suited to the last mile than any van. Of course, you’re probably thinking, “Well, what works in Europe won’t work here.” But, as Pembina showed, for all the differences in geometry—architecture and city layout—the real math comes down to density. A dense city shrinks distances—and shorter distances require different tools. This conceptual onboarding was key to Pembina’s approach.

Everyone Agrees on Cargo Bikes—But No One Agrees on How

Pembina hosted three seminars on this theme, each one drawing a larger crowd until the final event at the prestigious Globe and Mail Centre. The owners of Pedaal were present with cargo bikes at every meeting, and, having contributed to Pembina’s white paper, we also led several workshops and presentations. We met executives from UPS, FedEx, Purolator, and Canada Post. To our surprise, all agreed that cargo bikes were the future, but each raised the same obstacle: the unions. None could see how unionized drivers could be shifted onto cargo bikes—or replaced by workers willing to ride them. This, we realized, was a tricky problem indeed.

This problem is illustrated by another Canada Post strike at the time of writing. We are reminded of a conversation we had with a Canada Post executive at the Pembina meetings. For some background, the first Pembina event argued that cargo bikes are only one part of the solution. They cannot alone solve the problem of the last mile. A much costlier problem revolves around the creation of micro-hubs. Micro-hubs involve real estate, and Toronto real estate isn’t cheap. Yet, as our friend at Canada Post pointed out, Canada Post already had thousands of micro-hubs. They are called post offices. That meant that, in the case of Canada Post, the only thing missing was cargo bikes. We thought that was interesting!

The Geography of Gridlock

This is especially interesting because companies like FedEx have the cargo bikes but lack the micro-hubs. When FedEx launched its program in Toronto, the main depot in the Port Lands served as an East End micro-hub, but this hardly fit the ideal model. With an ideal micro-hub, the hub lies at the centre of a dense 5 km radius that a cargo bike can serve faster than a van. To some extent, the main depot worked as a micro-hub, but it was situated right next to Lake Ontario, meaning it only served a 180-degree radius.

On the west end of town, FedEx rented a Public Storage locker—again, hardly a permanent solution. Meanwhile, Purolator Courier established an almost perfect micro-hub at the centre of the University of Toronto, modelling the public-private partnership that FedEx couldn’t quite manage. But it’s only one micro-hub, and the program doesn’t appear to be growing. All of this produced an interesting picture. Canada Post had the largest network of micro-hubs, but no cargo bikes. FedEx and Purolator had the bikes, but not the micro-hubs.

Ratify Cargo Bikes!

In the case of Canada Post, the problem is not letter carriers. Letter carriers use the post office in the same way a cargo bike would use a micro-hub, and letter carriers remain an efficient part of the delivery ecosystem. The problem is that letter volume has fallen while parcel delivery has increased. And parcel delivery is not handled by letter carriers; it is handled by trucks. Here again: trucks get jammed in gridlock. And, these drivers are unionized and can’t flip so easily onto a cheaper and more efficient solution. Like we said: tricky.

So, how did FedEx jump into the cargo bike game so easily? Easy. FedEx isn’t unionized. That meant FedEx could innovate on its feet, and, if there’s one thing we admired about FedEx, it was its commitment to making innovation work by exercising careful due diligence. (Sidebar: the author was raised by a CLAC Union Rep and is definitely pro-union!).

The Bullitt Advantage: Small, Fast, and Built for the City

A crucial detail in this due diligence was the type of cargo bike. Pembina’s analysis showed that the advantages of cycling were lost when bikes started to look like trucks. If a truck wins on volume capacity, it loses in gridlock. A bike has far less volume, but wins in gridlock. There’s a sweet spot there, and the Pembina results showed that smaller, two-wheeled bikes have the data on their side. Whereas a van’s volume ensures it need not lose efficiency by returning and reloading at the main hub, a cargo bike returns and reloads constantly. This may seem inefficient, but bigger volume does not win the efficiency game. The bigger the volume, the more gridlocked packages get. Bikes keep things moving.

Luckily, by the time FedEx began exploring the cargo-bike option, Bullitt already had a strong foothold in Canada. The founders of Pedaal had been importing and distributing Bullitts to shops across the country since 2014, and in cities like Toronto and Montreal, independent courier firms had built their fleets entirely around the Bullitt bikes. Those early adoptions showed that the Bullitt could carry heavy commercial loads, withstand year-round riding, and deliver the efficiency that Pembina’s study described. When we started Pedaal, Bullitt followed the expertise.

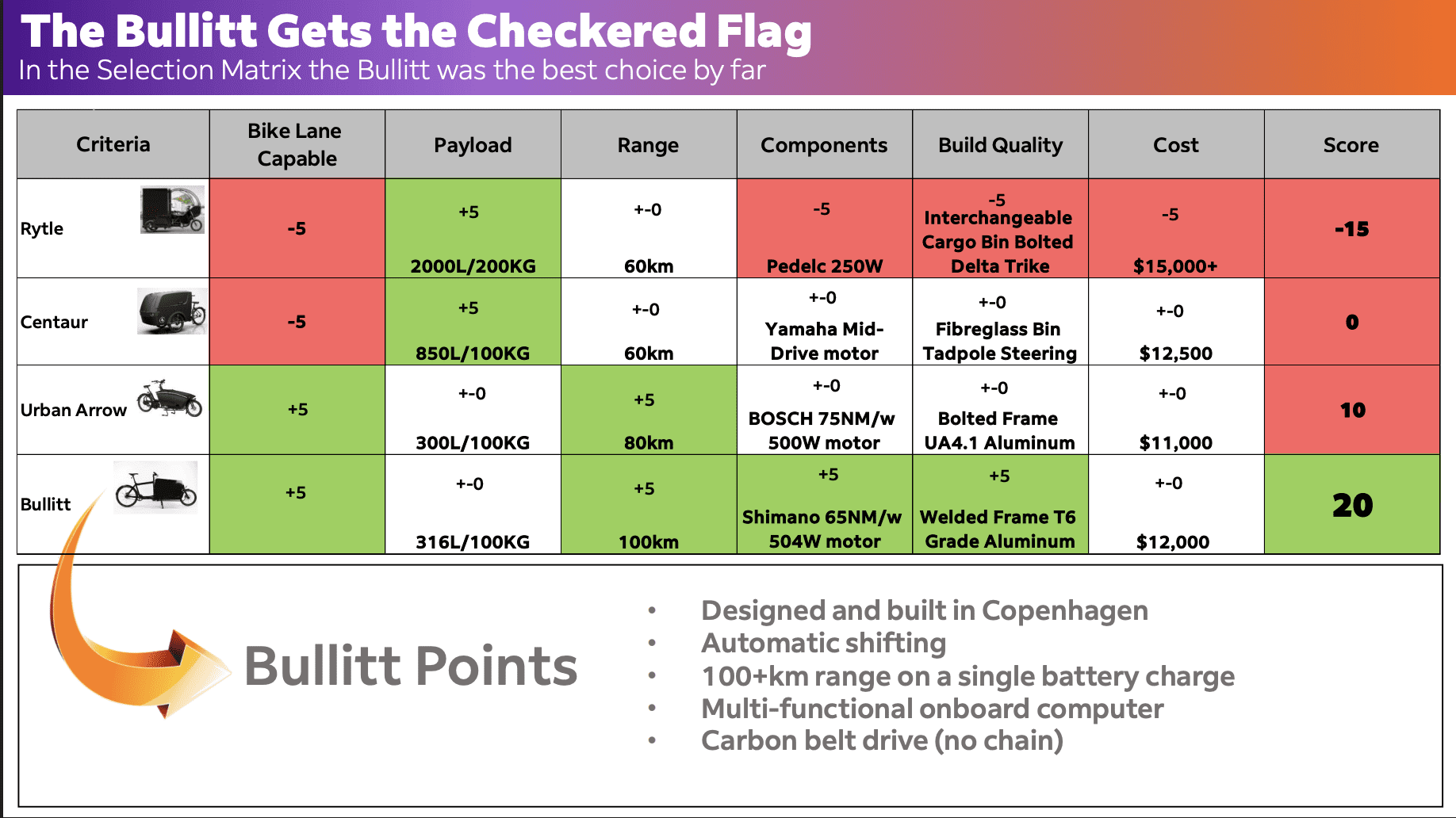

Bullitt Points: FedEx Does Its Homework

FedEx entered the picture through its participation in Pembina’s workshops. Two questions dominated: which bike could deliver consistently, and how to ensure future-proof, legal compliance. With the latter question, quite a few carriers had already stumbled. In 2017, UPS had rolled out oversized, throttle-based cargo bikes in Toronto that exceeded legal weight and power limits from day one. Purolator’s throttle-assist fleet is also extremely wide and sits in a regulatory grey zone. For FedEx, a long-term solution had to be efficient and future-proofed from all angles.

When the due diligence was complete, Bullitt was the obvious candidate. In many ways, FedEx followed companies like DHL, which also did their due diligence and use Bullitts across the EU. The Bullitt’s Shimano Class-1 pedelec motor meant it was pedal-assist only. That meant it was fully compliant with European regulations, which Canadian regulations are slowly inching toward. The one-piece aluminum frame made it the lightest in its class, while also being remarkably strong and stiff under load. Narrow and fast, it retained the defining advantage of the bicycle even when carrying heavy cargo.

The FedEx Pilot That Proved the Power of the Bullitt

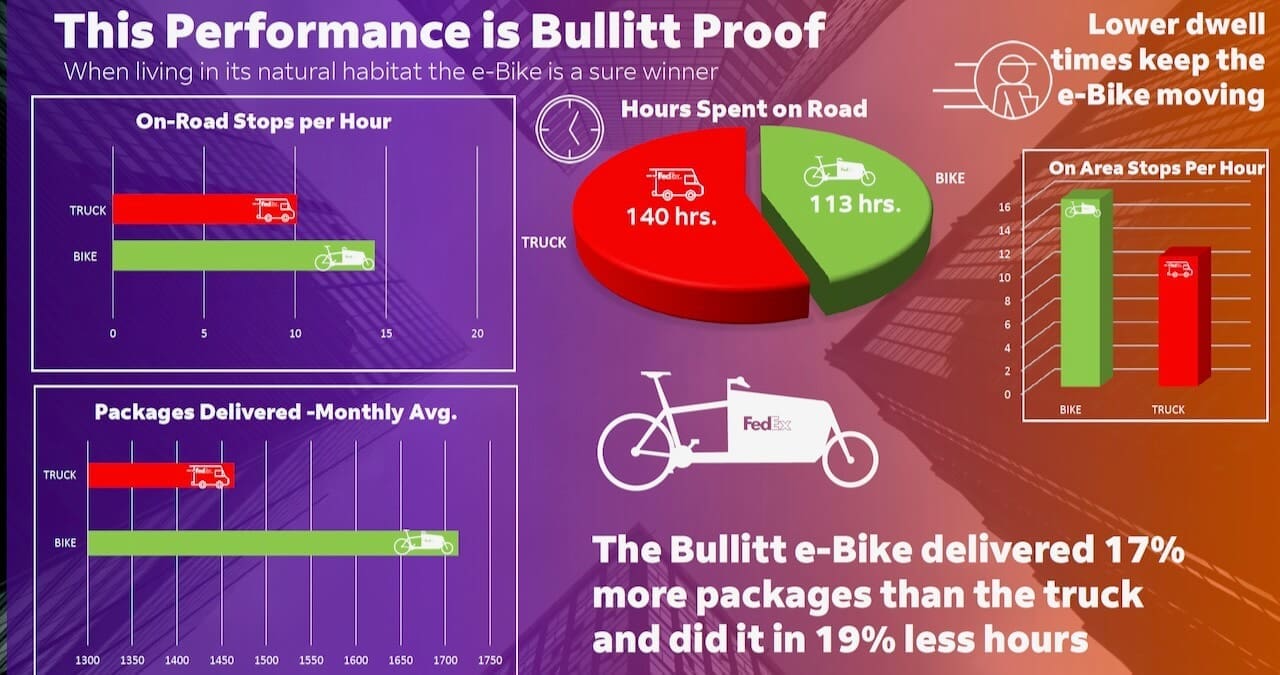

FedEx launched a pilot in Toronto with just three Bullitts, assigned to residential neighbourhoods like the Beaches, Danforth, and Rosedale—zones where vans struggled with parking and congestion. Within months, the results were in. Each bike consistently out-delivered a van, completing 17% more packages in 19% less time. Cost per package dropped by sixty-five percent, translating to annual savings of more than sixteen thousand dollars per bike. Maintenance was minimal: each machine averaged twelve thousand kilometres per year, kept rolling with nothing more than routine service. Parking tickets disappeared entirely. Perhaps most tellingly, customers began to notice and ask if all their deliveries could come by bike.

The success of the pilot led to rapid expansion. FedEx added more Bullitts in Toronto and quickly rolled out the model nationally. One hundred bikes were deployed across Montreal, Ottawa, Calgary, Vancouver, and Victoria—the single largest Bullitt order ever placed in North America. For the owners of Pedaal, it was the moment a decade of groundwork crystallized, the proof that years of advocacy and distribution had prepared the stage for a major logistics player to commit at scale. You can read the FedEx report here.

Fulpra: When Cargo Bikes Start Acting Like Trucks

While Purolator and FedEx both launched impressive fleets, neither fleet is growing. The main reason, we suspect, is that both got stuck with the cost of micro-hubs. But, at the same time, this problem also exists in Europe. The reality is, few companies want to invest in real estate, and we can’t blame them. A look at Europe shows that the companies that are growing are innovating beyond micro-hubs. This is interesting. If micro-hubs are a bit heavy-handed—a little too academic—then is there another solution? Indeed. And, it comes back down to the cargo bike.

FedEx clearly saw this issue themselves. In 2023, FedEx leased three Fulpra cargo bikes—huge-capacity bikes that look like small trucks. These bikes were bought to increase volume and reduce re-ups at the main hub. These bikes can often be seen on Toronto’s Martin Goodman Trail, a car-free cycle path that is doorstep to a multitude of condo buildings. But, rarely do these bikes venture downtown. Why? Because they have the same problems as a van. Just like a truck, because of their width, they get stuck in traffic.

The Narrow Truth

FedEx was right to increase the cargo bikes volume capacity, but the problem of gridlock cannot be answered with something wide. Bullitts, for instance, are 46 cm—a width that Bullitt is nearly religious about. Why? Because a 46 cm bike can be deployed into almost any city worldwide with bike lanes and still pass and be passed. The wider a vehicle is, the more likely it is to get stuck. The narrower a bike is, the more it can squeeze through things. The lesson, it seems, is to build volume across length, not width.

Turns out, FedEx may already have had the answer. Or, part of it. They just needed to watch the trailer, if you will, for all the developments happening in Europe. One of the fastest-growing cycle-logistics companies in Europe is Urbike in Brussels. They don’t use micro-hubs. Like FedEx, Urbike has a fleet of Bullitts. The difference is that they add a trailer.

Watch the Trailer

The beauty of a trailer is that it can lengthen a bike without adding any width, and, in the case of Urbike’s Flexi-Modal trailers, they turn in perfect symmetry with the bike, so the trailer does not demand hitting the brakes in high-speed corners. Best of all, a trailer is incredibly low-tech. The Fulpra bikes that FedEx is experimenting with currently have a high degree of proprietary parts, an equally high degree of motorcycle parts, and a lesser degree of standard bicycle parts. Few bicycle mechanics can fix these bikes from a plug-and-play perspective.

The best part about using a trailer compared to using a bike like Fulpra is that a trailer is low-tech and far more modular. The bike courier can detach the trailer at the depot if the next trip has less volume, and can attach it again if the following trip has more volume. Likewise, at the depot, trailers can be preloaded before the driver arrives, saving valuable packing time. Best of all, when it comes to the problem of the “last steps,” a trailer can detach and be walked into a condo lobby, reducing the back-and-forth between the cargo bike and condo mailboxes.

Let’s Build Your Bullitt Fleet

Pedaal is the authorized distributor of Bullitt cargo bikes in Canada, and we’ve been part of this shift since the beginning—long before the first FedEx pilot or the first policy study. Over the years, we’ve helped everyone from local couriers to major logistics firms build their fleets, and we’ve seen first-hand how a well-built cargo bike can change how a city moves. Today, we’re proud to say that no one in Canada has more experience with Bullitts than we do. We handle everything—assembly, customization, fleet scaling, and nationwide shipping—and we back it all with competitive B2B pricing and reliable service through VeloFix partners across the country.

So if you’re a business ready to move faster, cleaner, and smarter, email eric@pedaal.com. Whether it’s one bike or one hundred, we’ll help you build a fleet that’s ready to work—and ready to earn—on day one.

Bikes for business inquiries

"*" indicates required fields