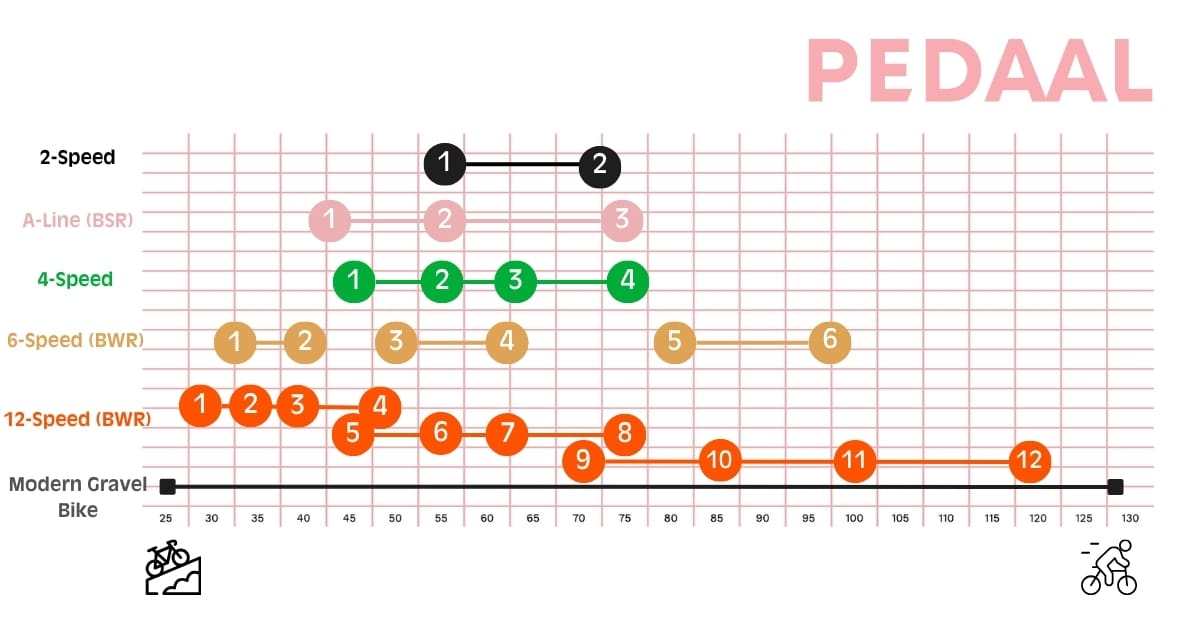

For years, the Brompton 6-speed was the go-to choice for riders who wanted a folding bike with enough gears to handle hills and longer rides. But with the launch of Brompton’s new 4-speed and 12-speed drivetrains, the old 6-speed is now obsolete. The 4-speed offers a lighter, simpler solution for city commuters, while the 12-speed delivers a wider gear range, smoother shifting, and less complexity than the system it replaces. Together, they mark the beginning of a new generation of Brompton bikes – and the end of the 6-speed era.

How Brompton Outgrew the BSR Hub

The story of Brompton gears is really the story of how a small folding bike grew up. When Brompton first appeared in the 1980s, it relied on a simple and robust piece of British engineering: the Sturmey-Archer BSR 3-speed hub. For urban cycling, an internal gear hub is nearly perfect. It seals away the moving parts from grit and rain, demands almost no maintenance, and keeps working in all weather, year after year. No other drivetrain system in the bicycle world has proven itself as reliably.

But the BSR hub had a problem. Its three gears didn’t give riders enough range. At the low end, it ran out of help on serious climbs. At the high end, it spun out once you reached around twenty kilometres per hour. The reason was simple: the BSR was built for the Dutch, who ride heavy city bikes at modest speeds. The first two gears were designed to get a big steel Dutch bike rolling and then keep it rolling. They weren’t designed for a nimble folding bike tackling the steeper hills of London, San Francisco, or even Toronto (we have a few!).

Brompton’s Clever Hub Solution

Brompton could have chosen a different hub with more gears. For instance, 5-speed, 7-speed, 8-speed and even 14-speed hubs were already on the market. But more gears always meant more weight. A three-speed hub weighed about three pounds, while an eight-speed came in around eight. Adding that kind of weight to a bike designed to be carried up staircases and onto trains simply wasn’t an option.

So Brompton did something else. Working directly with Sturmey-Archer, they designed a new hub that looked and weighed the same as the old BSR, but inside had the same 306% gear range of an eight-speed. This was the BWR hub, and it was a masterstroke. For the first time, a Brompton could take on long climbs without giving up portability.

The Classic 6-Speed: Brilliant, But Not Perfect

The BWR, however, created a new problem. Its three gears were so far apart that riders often found themselves in the wrong place between one gear and the next. To fix this, Brompton added a tiny two-speed derailleur, which effectively filled in the gaps and created the classic 6-speed Brompton.

For its time, the 6-speed was brilliant. It gave Bromptons the range to tackle hilly cities and opened up the possibility of longer trips. But it also came with compromises. Shifting almost always meant clicking both shifters in sequence to land on the right gear, and the gaps in the range still felt uneven. There were moments when no gear quite fit, which became frustrating for daily riders.

Range for the Road

Still, the 6-speed reflected Brompton’s conservative design philosophy. The company wanted to improve the bike without altering its fundamental structure. Working a new hub within the same narrow rear frame was already an achievement, and squeezing in two tiny cogs for the derailleur required ingenuity. For years, the 6-speed was the right answer. But as riders began taking their Bromptons further – onto planes, and on epic bike tours – the limitations became clear.

It was for this rider, the one who wanted a Brompton not just for the “last mile” but for longer rides, that the Brompton G-Line was created. Yet not everyone needs a G-Line. Many still prefer the classic Brompton that folds small enough to slide into an overhead bin. What these riders wanted was a drivetrain that offered more range, smoother progression, and less complication. The answer is the new generation: the 4-speed and the 12-speed.

The Next Gear Up

The 12-speed still uses two shifters, but in practice it’s far simpler than the old 6-speed. The three-speed hub now works more like a front derailleur on a traditional bike, offering low, middle, and high ranges. Within each of those ranges sits a four-speed cassette that provides smooth, incremental steps. Most of the time, riders stay on the hub’s second gear and use the four-speed shifter, only tapping the hub when they need a big change. It’s a system that feels intuitive, seamless, and powerful. The range is broad enough to climb almost anything and fast enough to keep up with city traffic, all while eliminating the frustrating gaps that defined the old 6-speed.

The 4-speed brings Brompton back to its roots as a city bike. From the start, Brompton has been invested in building the most capable tool for replacing walking, driving, or public transit. Early models relied on the BSR hub, which provided a practical gear range but added unnecessary weight. The new 4-speed removes the internal hub entirely, offering the same useful range as the BSR at a fraction of the weight. Where the 12-speed expands the Brompton into longer distances and steeper terrain, the 4-speed is a nod to the city rider who values simplicity, portability, and just enough gearing to handle everyday streets.

The 4-Speed Revelation

If the 4-speed is revolutionary for the same reason as the 12-speed, it’s because previous attempts to lighten the 6-speed bike never quite succeeded. The old 2-speed eliminated the internal gear hub, but its two gears were so close together that it added complexity without real benefit. The 6-speed improved range, but at the cost of extra weight and awkward shifting. Even the A-Line, which offered an ideal range between the 2-speed and 6-speed, relied on the heavier BSR hub. The new 4-speed finally gets it right. It’s lighter than the internally geared hub models, more practical than the 2-speed, and far more elegant than the 6.

For the city cyclist who is buying the Brompton as a tool, nothing more than a decent spread of gears is required. That rider may already own another bike for longer distances, whether that’s a road bike, gravel bike, or mountain bike. For them, the 4-speed is the perfect complement: a compact, efficient tool for urban life. The buyer of the 12-speed is investing in both a tool and a recreational platform, while the buyer of the 4-speed may only need the tool – and choose a Brompton precisely because it is cheaper, more joyful, and more efficient than transit or driving. In many ways, the 4-speed is the purest expression of Brompton’s mission: to make everyday city travel simple, practical, and fast.

The End of an Era

These new drivetrains required more than clever engineering. They demanded a redesigned rear frame, one that could accommodate four cogs instead of two and provide greater strength around the roller wheels. This frame, code-named the MK6, quietly marks the beginning of a new generation of Brompton bikes. Technically, an older 6-speed can still be converted to a 12-speed, but the cost of replacing the frame, the wheel, and the drivetrain runs well over fifteen hundred dollars. In practice, the 6-speed belongs to the past. Meanwhile, at the time of writing, other stores are selling the 6-speed for $2685 whereas the new 12-speed goes for $3000. So unless you’re eager to relive the days of awkward gaps and double-shifter gymnastics, the 6-speed is really just a reminder that Brompton has already moved on.

And that’s the real story here. The 6-speed was a bike of its time, a clever solution that carried Brompton through decades of growth. But it was always a compromise. The new 4- and 12-speed models remove that compromise. They are smoother, lighter, stronger, and better suited to the way people actually ride Bromptons today – whether that means commuting across a dense city or climbing hills in the countryside.