If you live downtown, you may already be a city cyclist without realizing it. Canadian cities are in the midst of a Great Reset. People are choosing proximity over sprawl and community over commuting. But as our lives reset around local shops, short trips, and denser neighbourhoods, have our ways of moving kept pace? Or, have we sabotaged ourselves by holding onto old habits? For decades we’ve been told cars are necessary and bikes are for recreation. Yet what if the opposite is true? What if bikes are essential because they solve the majority of your daily trips, while cars are best reserved for the occasional journey out of town? If the Great Reset is tied to a higher quality of life, how do we bring quality to our movements between errands, work and play? We might want to begin by qualifying our options! So, let’s do just that.

Walk Scores and the New Urban Value System

The clearest way to see this Great Reset is through Walk Scores. They measure property value, proximity, and the distance of everyday trips. Once seen as a drag on real estate, Walk Scores now capture the premium people place on being close to what they need. Higher scores mark dense, diverse neighbourhoods where every trip runs past cafés, shops, parks, or services. The old myth of the car is slipping, replaced by a new economy of convenience, connection, and urban variety.

Richard Florida frames this transformation through three overlapping shifts. Economically, access to jobs, amenities, and knowledge networks concentrates urban density. Demographically, younger professionals and families increasingly prefer proximity, diversity, and shorter commutes. Culturally, people seek walkable, socially connected neighbourhoods.Local shops edge out chains, tree-lined streets invite neighbourly encounters, and walkable blocks turn errands into moments of connection. Gentrification is the downside, but these same forces create the perfect conditions for cycling. (As seen in Columbia, cycling can have a democratizing impact).

Suburban Hangovers

Walk Scores are often cited as a measure of neighbourhood convenience, but the term can be a bit of a misnomer. Many of the distances they highlight are way far to walk comfortably. As this study shows, Walk Score treats being within a 30-minute walk as “walkable,” but most people won’t regularly walk that far for errands. At the same time, these distances are too short to make driving worthwhile. Nonetheless, we can call it a hangover from the suburban mindset: but, people continue to drive.

According to the National Household Travel Survey, nearly 50% of all trips are three miles or less, yet fewer than 2% of those trips are made by bicycle, while 72% are driven. Toronto now has the world’s third-worst traffic, costing $44.7 billion a year and stealing 98 hours from the average commuter. Yet, this problem is easily solved with a bicycle.

The Cost of Gridlock: How Bikes Keep Cities Moving

That’s because cycling excels precisely where walking and driving are both inefficient. The Dutch know this very well. The Dutch seem to have a clear-eyed and tool-based approach to the bicycle and the car. Instead of terms like “the last mile” – which isn’t an actual mile – or Walk Scores for distances that aren’t walkable, the Dutch look at the range in which bikes outcompete cars and the range in which cars seem to outcompete bikes. Then they crunch the numbers. The range these studies produce are directly transferable to North America. Where urban density is similar, a bike conquers the same amount of ground. In fact, it was the same Dutch data, incorporated into the Pembina Institute’s study of last-mile logistics, that prompted FedEx in Canada to buy a fleet of 100 Bullitt bikes.

We might want to take the FedEx example seriously. After all, the difference between FedEx and a typical car driver downtown is that a private driver may endure traffic, gridlock, parking and costs. They might hate it, but they also continue to afford it. For FedEx, however, time in a van stuck downtown is something they cannot afford: every delay in traffic is a direct cost. Vans gridlocked in urban cores don’t make money; bikes, on the other hand, move quickly, reliably, and without the same overhead, making them the optimal solution for dense, short-distance logistics. You might be able to afford driving, but imagine what you might be able to afford even more by cycling.

Mapping the Great Reset

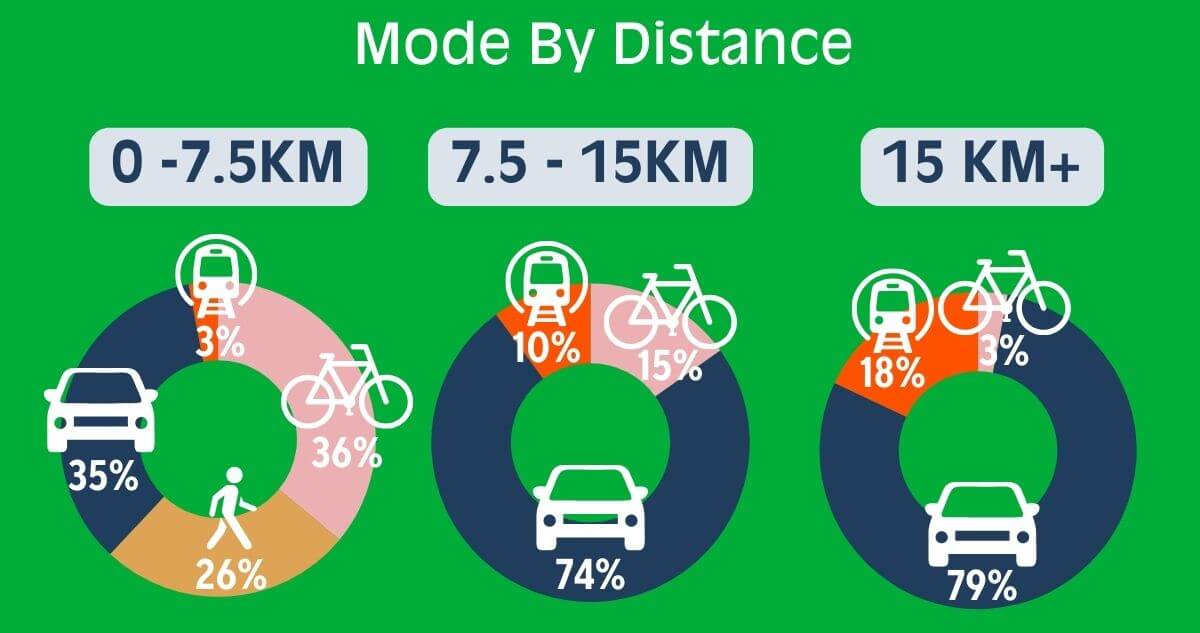

The Dutch model breaks trips into three rough categories: under 7.5 kilometers, between 7.5 and 15 kilometers, and over 15 kilometers. This helps us understand where bikes win and where cars win. Each, after all, are legitimate tools. In dense urban centers, the overwhelming majority of your trips will fall under 7.5 kilometers. This is the distance perfectly suited to cycling. Meanwhile, trips over 7.5km see an exponential increase in car use. Why? Because when it comes to longer distances, a car will always win. All of this helps reduce ideology around drivers who see a “war on the car” or zealous cyclists who want a car-free world. Consider that in Holland, both bike ownership and car ownership are the highest in Europe. We might want to view this complementarianism as the key to freedom. Freedom, after all, is intricately tied to mobility.

Using this “under 7.5 km” range helps add some empirical distance to many of the misnomers presently being employed. Again, “the last mile” is never an actual mile, and walkability is often less walkable than the term suggests. The Dutch framing, by contrast, offers an empirical and clear-eyed view of where bikes excel and where cars take over. It also helps downtown residents recognize their place in the Great Reset: if your routines revolve around short, concentrated trips, you’re already part of the demographic reshaping city cycling.

Navigating the Last Mile

Dock to Dock

While FedEx is one example, Toronto’s Bike Share program is another empirical way to see how this 7.5-kilometer metric plays out locally. The average trip is about 3.3 kilometers, lasting roughly 20 minutes. The system encourages short, transportation-based rides – distances too far to walk and too close to drive – and penalizes longer, recreational use with exponentially rising overage fees. In other words, bike-share systems are designed primarily to provide affordable, short-distance urban transport, functioning like public transit and reducing reliance on private vehicles. This mission underpins the short-trip pricing model.

Now, Bike Share programs typically operate dock-to-dock: bikes are picked up and returned at fixed stations. As public systems, they remove the responsibility of ownership and offer flexibility, but they are less convenient than other options. After all, riders must contend with dock availability, maintenance issues, or broken bikes, and there is always the extra walk to the nearest station. If Bike Share solves the so-called “last mile,” it doesn’t solve what theorists call the “last meter.” (For companies like FedEx, those final 100 meters to the drop-off add another layer of cost and delay). Like driving or transit, you still end up walking these “last meters” to the parking garage, the bus stop, or the bike dock.

Door to Door

By contrast, consumer-owned bikes most typically offer door-to-door use. Most bikes sold at traditional shops are effectively door-to-door: they are meant to ride outdoors, be locked outdoors, and “live” outside. While convenient, this exposes them to constant theft risk. Bringing a bike indoors offers more security, yet most Toronto bicycle thefts now occur in underground garages, including condo and office parking.

Although technically “inside,” these spaces are far less secure than bringing a bike really inside – that is: your own apartment, office, or shop. But, the challenge is that many condos prohibit full-sized bikes in units. This helps explain why Bike Share is popular – and also why we sell so many Brompton folding bikes. A Brompton can be carried past the condo concierge, stored neatly in a closet, and tucked away without cluttering small spaces. It is the very definition of a desk-to-desk bike, solving problems that neither Bike Share nor full-sized bikes can.

Desk to Desk

And so, a desk-to-desk bike represents the ultimate solution for city cyclists. Unlike Bike Share or conventional bikes that spend most of their lives outdoors, it is designed to live indoors. This points out the fundamental difference between the city cyclist and the recreational cyclist. The recreational rider, after all, leaves the indoors to travel more than 7.5 km into the great outdoors. That’s the whole point! The city cyclist, on the other hand, leaves indoors only to return indoors – whether for work, the gym, or groceries. Thus, it is arguable from a use-case perspective that a true city bike will handle the indoors as well as the outdoors. In this respect, Brompton has mastered that balance. Of course, a desk-to-desk bike is not just more convenient than a door-to-door bike; it also minimizes theft anxiety and eliminates the last-meter inconvenience of dock-to-dock systems.

From Train to Desk: The Origins of the Brompton

If a Brompton has mastered the use case for the city cyclist, it’s because the company explicitly started with the goal of solving the so-called “last mile.” Originating in London, the Brompton was first designed for train commuters. London, after all, expanded its boundaries via train, not car, and while trains were fast and convenient, the stations themselves could be too far to walk from home or work, yet too close to justify driving. Once again: the problem of the “last mile.”

The same thing is true in Canada. Think of the huge parkades at GO Train stations along the Lakeshore – built for people who bought a car just to get to the train. Brompton answered this problem by building a bike that could go inside the train and then, once at home or work, inside there too. This focus on indoor use continues to set Brompton apart from all other city bikes on the market. If you take the Go Train you might spot a Brompton by someone who saw the same logic for themselves. It’s a real game changer!

Why Traditional Bike Shops Don’t Serve the City Cyclist

The Great Reset may be happening, but it still takes time for all the resets to occur. Indeed, if people are still driving in the last mile, it’s often because they haven’t fully embraced the Great Reset. And, the same is true for most bicycle stores. While cities pour resources into Bike Share programs and protected lanes to encourage short urban trips, many bike shops still resemble suburban outposts. Floors are filled with road, gravel, and mountain bikes – machines designed for recreation and distance, not the shorter 7.5-kilometer trips that define city life. For decades, the North American bike industry treated bikes as sporting equipment, not transportation, creating a cultural blind spot.

Of course, one reason traditional bike shops rarely carry true city bikes is risk: these bikes are designed to live outdoors and are what we call door-to-door. That makes them more vulnerable to theft. At the same time, many shops feel they cannot compete with Bike Share programs, both in terms of convenience and in terms of overall quality. So if you walk into a bike shop wondering why they aren’t providing city bikes, this helps explain that. But, that’s exactly why stores like Pedaal exist. We’re here to provide real solutions while providing the thought leadership our industry needs!

Meeting the Last-Mile Challenge

At Pedaal we believe that a city cyclist is not a “cyclist” in the enthusiast sense. They are someone navigating the last mile of daily life – getting to work, groceries, school, or the gym – and they represent a far broader demographic than our bicycle industry has ever acknowledged. This is the blue ocean the Great Reset points toward, and the future the bike industry has yet to catch up to.

We believe that if a store wants to sell city bikes, it has a responsibility to analyze the actual use case of a city cyclist. This is especially true if they want to compete with Bike Share programs. This includes understanding the critical role theft plays when a bike must live outside. Desk-to-desk bikes, like Brompton, meet this requirement perfectly: they fold compactly, travel with their rider indoors, and eliminate exposure to theft entirely. They are explicitly designed for trips under 7.5 kilometers, though they are fully capable of longer rides if you have a big European trip planned. For downtown residents whose lives revolve around short, concentrated trips, a Brompton is the optimal solution.

Why Some Bikes Can’t Go Desk-to-Desk

As we’ve seen, when theft is a design constraint, city bikes should probably not be door-to-door machines. If you do use a regular bike, the battle against thieves can be won, but the cost is high. Today, thieves cut through expensive locks with cheap lithium-ion grinders. And so, the only guarantee is a $500 anti-grinder lock. But, for most standard bikes, we realize this hardly makes economical sense. As we’ve argued, desk-to-desk bikes, like the Brompton, solve this by traveling indoors with the rider. Dock-to-dock systems also mitigate theft, but they do so at the cost of private ownership and spontaneity. Each approach represents a distinct design principle, with only desk-to-desk or dock-to-dock truly addressing theft in urban cycling.

However, cargo bikes are the exception here. They simply cannot be brought indoors like a Brompton, yet their ability to carry groceries, kids and cargo makes them the one door-to-door exception. A cargo bike is exceptional because it glues the last mile together with exceptional carrying capacity. Hauling children, groceries, or other heavy loads has often been used to justify keeping a car for short urban trips. But, a cargo bike challenges this logic. A cargo bike offers an economical solution that glides through gridlock, eliminates parking headaches, and vastly reduces ownership costs when compared to a vehicle. And, unlike a regular bike, their higher cost makes robust theft protection economically sensible. In the case of a cargo bike, a quality lock will only represent 5–10% of the bike’s value.

In Conclusion

As we’ve seen, chances are you already are – or could easily become – a city cyclist. If you live downtown and navigate short trips under 7.5 kilometers, whether commuting, running errands, or picking up groceries, you fit the profile perfectly. Dutch studies provide the empirical clarity that terms like “last mile,” Walk Scores, and the fifteen-minute city often lack. Most so-called walkable distances are actually too long to walk comfortably, and fifteen minutes rarely reflects real travel patterns. The Dutch data shows where bikes truly excel. These are short urban trips that make up the majority of your urban life. You don’t need a car for that.

Of course, owning a car is still an option. But, a car only makes sense for longer trips. In the end, this is not a choice of cars versus bikes, but a recognition that each tool has strengths in particular ranges. A multi-tool approach to urban mobility – a bike for short trips and a car for long ones – is the key to freedom and mobility. So, whether you choose bike share, a Brompton, a cargo bike, or a secure traditional bike, the right solution lets you move smarter, reclaim hours lost to traffic, and truly enjoy the diversity of life in the last mile.